It's About Time

Tempo in Chess and Old School Magic

By stsully

January 24, 2020

The concept of tempo in Magic comes up from time to time, and recently it has come up several times in the Old School social media multiverse. Tempo is a complicated subject in all forms of Magic, Old School included, but a lot of the confusion it can cause is simplified if we talk about tempo in another game first: chess. In fact, I would be shocked if the reason people even talk about tempo in Magic wasn't that people who played chess mapped tempo concepts onto Magic.

In this article, we'll look at tempo in chess, examine some analogies in Magic, and finally discuss some specific tempo cards played in the Old School Magic format. Also, note that this article assumes a basic familiarity with the rules of chess -- like, you're good enough to sit down and know how the pieces move and so forth -- but not any particular level of mastery. We'll walk through positions and moves with a lot of how's and why's.

Tempo in Chess

Tempo is one of the fundamental elements of analytical chess (some examples of others include material, development, and position). Tempo, which simply means "time" in Italian, is essentially a single turn or move in chess. On each player's turn, they are allowed to make a move. We can think of a chess player as receiving one "unit of movement" at the start of their turn, and then spending that unit of movement during their turn. Their opponent then receives a turn and a unit of movement. We simply call one of these units of movement a "tempo." A tempo is the "energy" or "power" of being able to make one move, and chess players always gain one tempo per turn.

While most of the time players simply make moves back and forth, gaining and then immediately spending their tempos, it is actually possible to gain or lose tempo over a series of moves. In fact, recognizing opportunities to gain (or even lose) tempo on your opponent is a tactic which can decide a game.

How can a player gain or lose tempo? Let's look at a few examples.

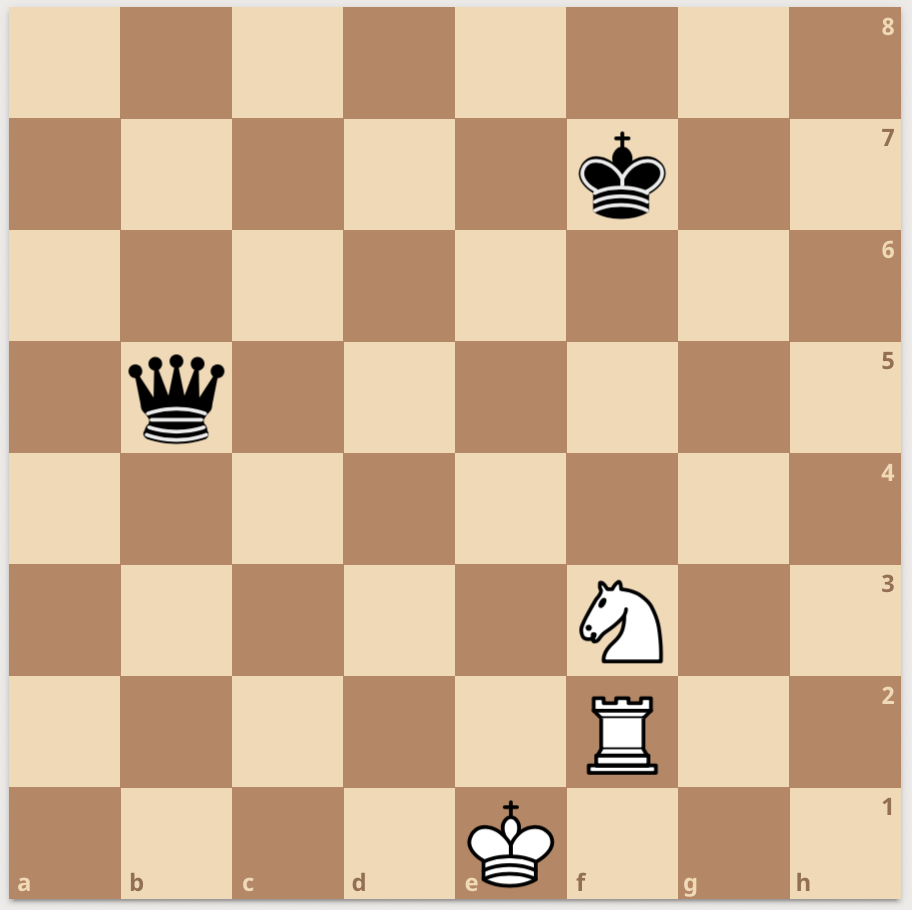

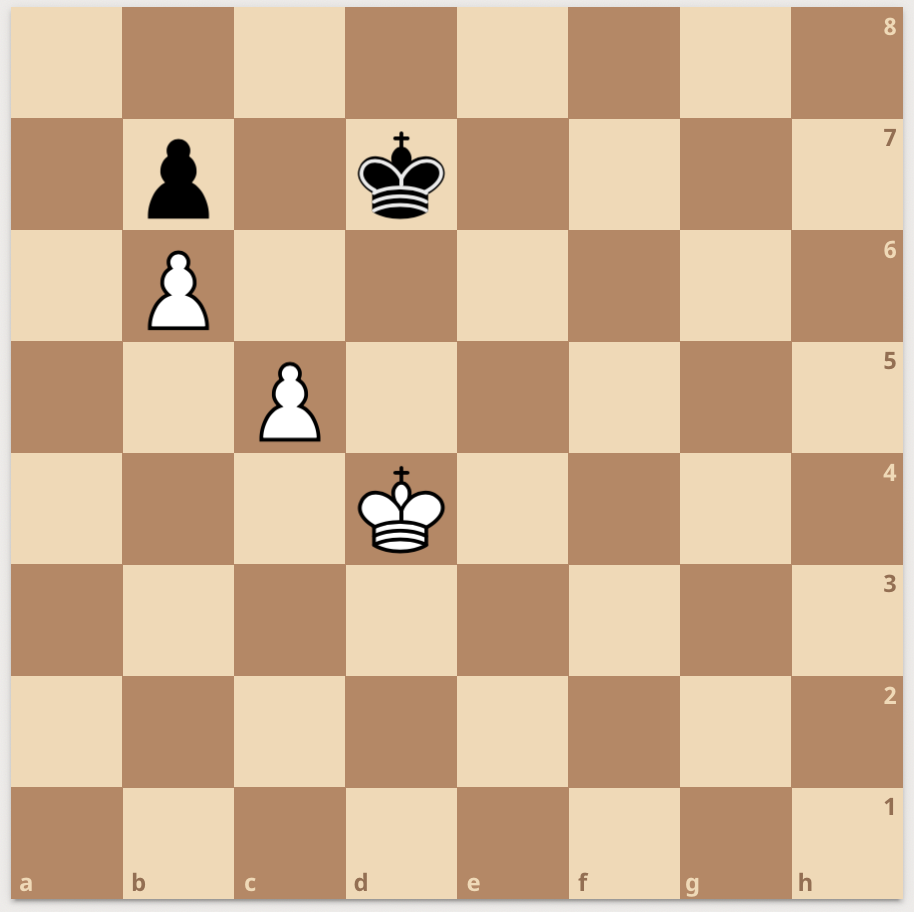

First, let's look at this position, with White to move:

1. e4 e5 2. Nf3 Nc6 3. Bb5 Nf6

This is a classic setup: the Ruy Lopez opening, aka the Spanish Game (specifically, the Berlin Defense of it), a popular and well-studied system. But let's suppose White isn't particularly well versed in the theory, and they decide they don't like the idea of Black capturing one of their pawns so early. So, they make this simple move, which protects the pawn on e4, but gives away the pressure on the c6 knight:

4. Bd3??

When White does this, they lose a tempo. Why? Because they moved their bishop back to a space it could have moved to in the first place. If they had wanted their bishop on d3, they could have gone there instead of b5 on their third move. That White spent a turn to move Bb5 is now wholly irrelevant.

Aside from the fact that d3 is currently a bad place for their bishop, the lost tempo creates an immediate positional disadvantage because it allows Black to develop their kingside knight for free. In fact, by developing he knight and attacking the pawn with Nf6, Black goaded our naive White player into losing a tempo in response. (Incidentally, White's canonical response is castling, 4. 0-0, knowing they can eventually win their e4 pawn back by taking the e5 pawn if necessary, which produces a dynamic game. Other moves like 4. Nc3, 4. d3, and 4. BxN are trodden lines too.)

Let's make things even worse for our friend White. Suppose Black responds to White's bishop move with the following (somewhat strange, for it creates risk for their knight) move:

4. ...Ng4?

And now suppose our friend White realizes his pawn is safe again, so he wants to put his bishop back on b5 to attack the knight like so:

5. Bb5??

White has lost yet *another* tempo, this time by moving the bishop back to where it originally moved in the first place!

Look at White's board. It's exactly the same as it was after their first three moves. Black, meanwhile, has gotten two extra moves with their kingside knight. While this is a funny position, Black is likely ahead. "Black is up two tempo," we can say, or "White has lost two tempo," though note that we would not say Black has "gained" any tempo, because they didn't really do anything to earn tempo themselves. The kinds of mistakes White is making here are common in novice games, because tempo in chess is not innately intuitive for most people. But once you know what to look for, they are glaring errors.

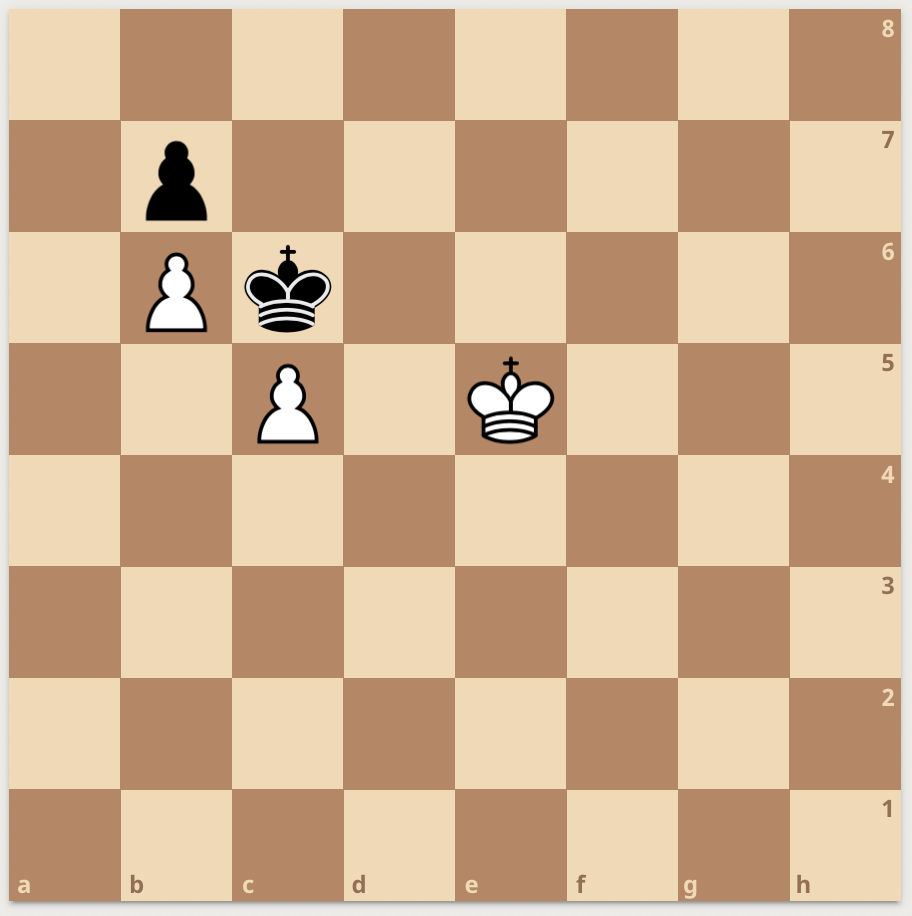

Now let's look at a position where White can actually earn a tempo:

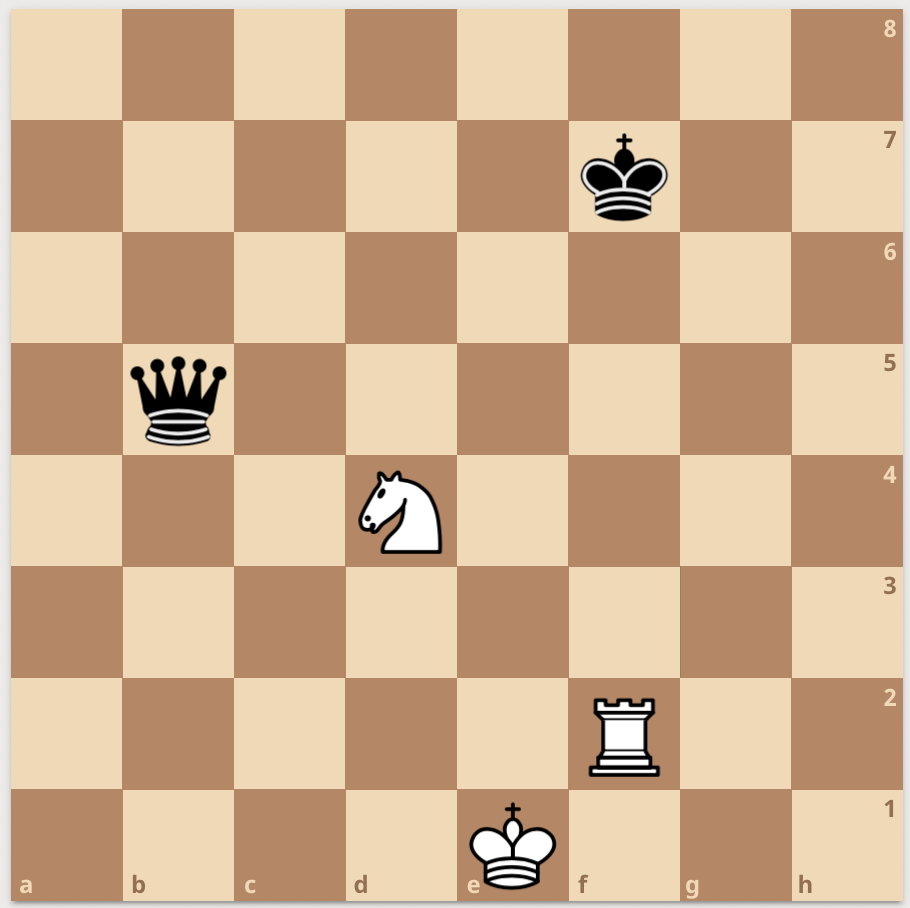

White to move

White is able to win the game with a discovered check, a powerful tactic which often generates tempo:

1. Nd4+!

White moves his knight out of the way of his rook, revealing an attack by the rook on the Black king, while simultaneously putting the knight into a position where it attacks the queen! Black is required to get their king out of check, limiting their ability to respond to the simultaneous attack on their queen. And while they can move their queen to block the check, it does nothing to remove her from danger because she can merely throw herself, unprotected, in front of the King for one turn. If only Black could make two moves in a row, they could escape, but alas, they can only make one move because chess players only get one tempo per turn. In this situation, we say "the knight has attacked the queen with tempo," winning the game in the process.

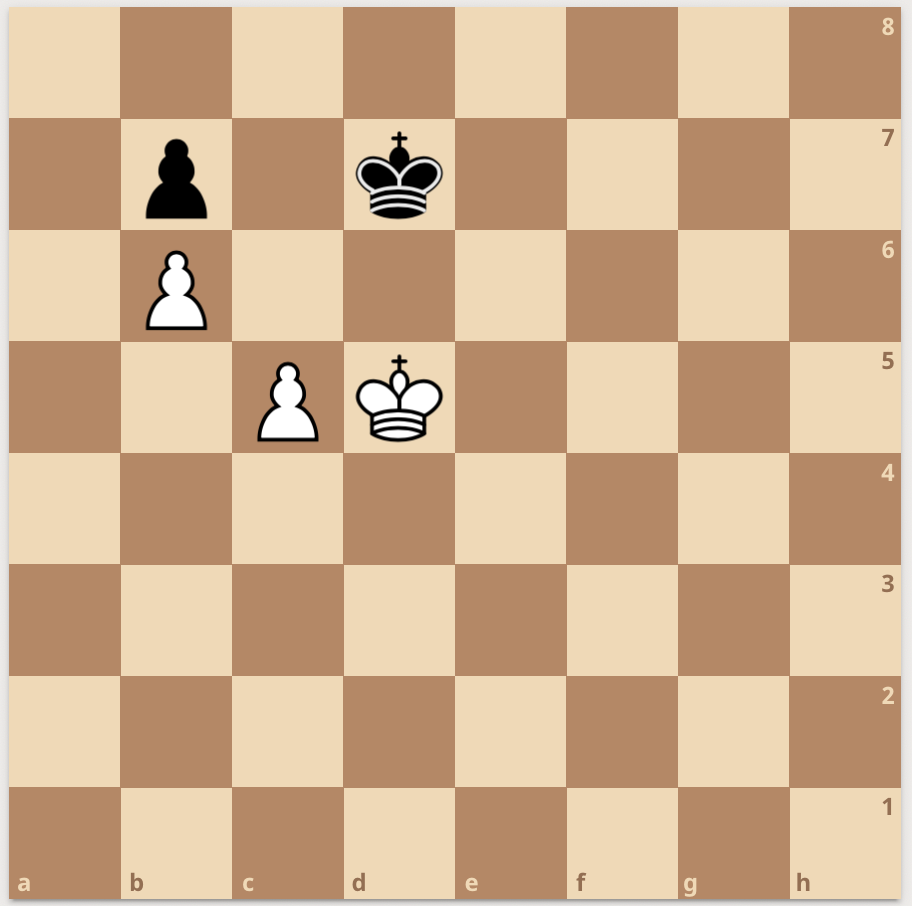

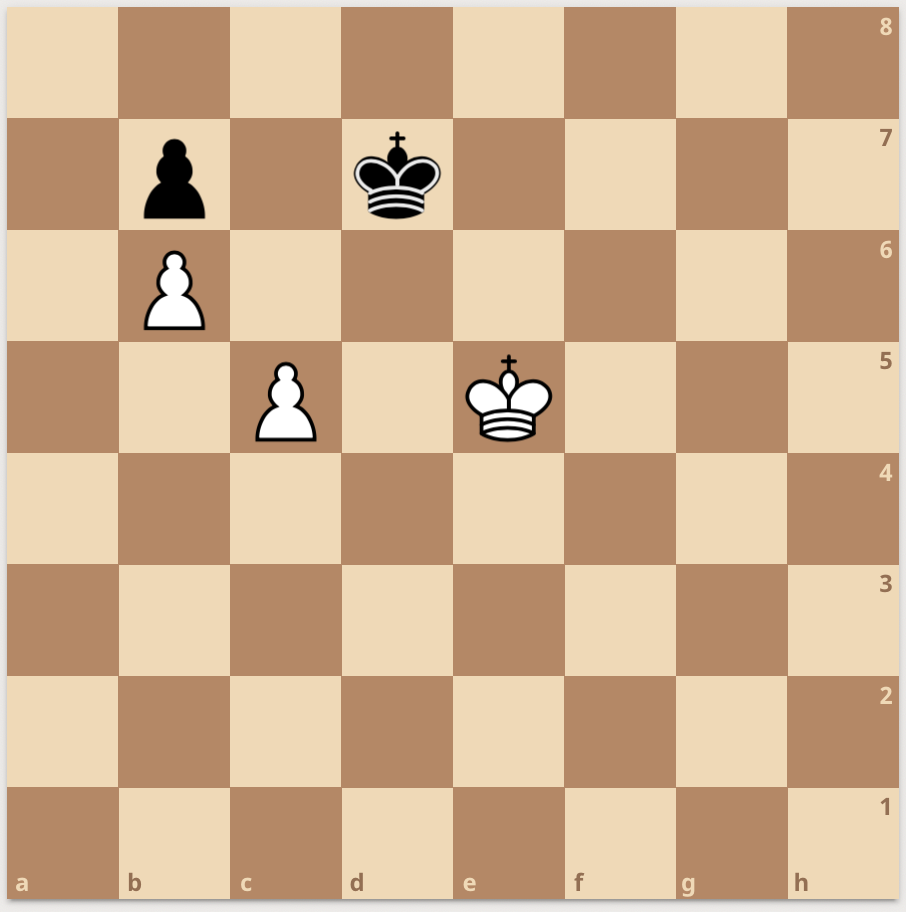

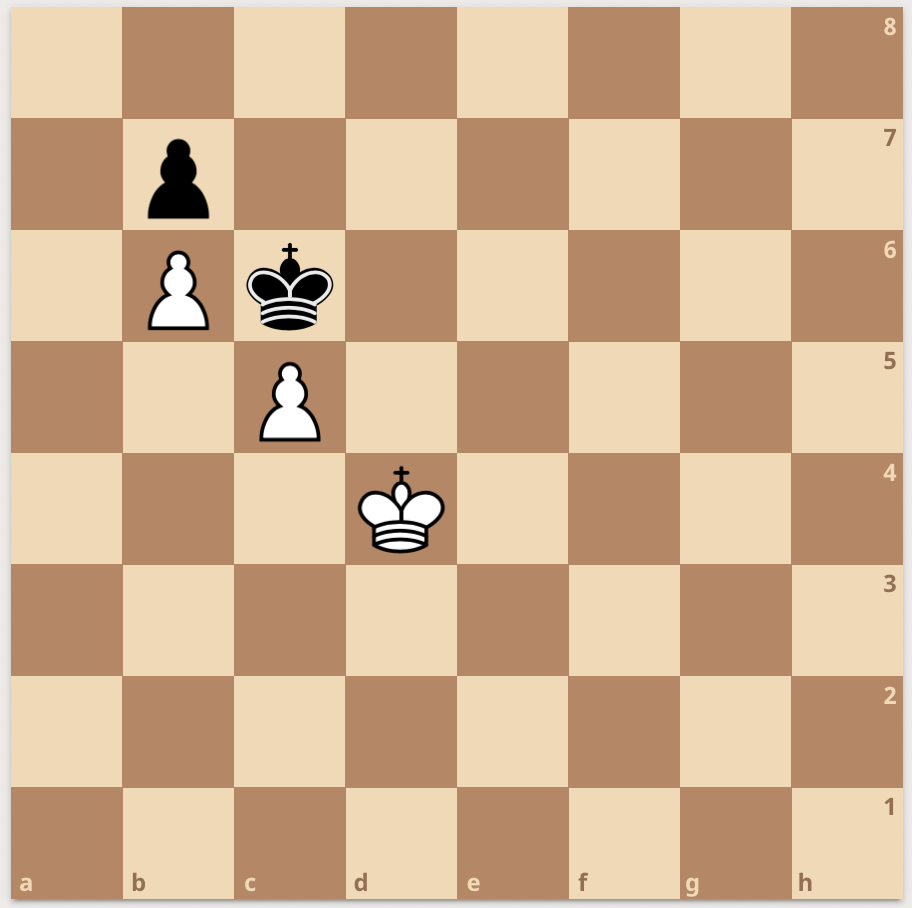

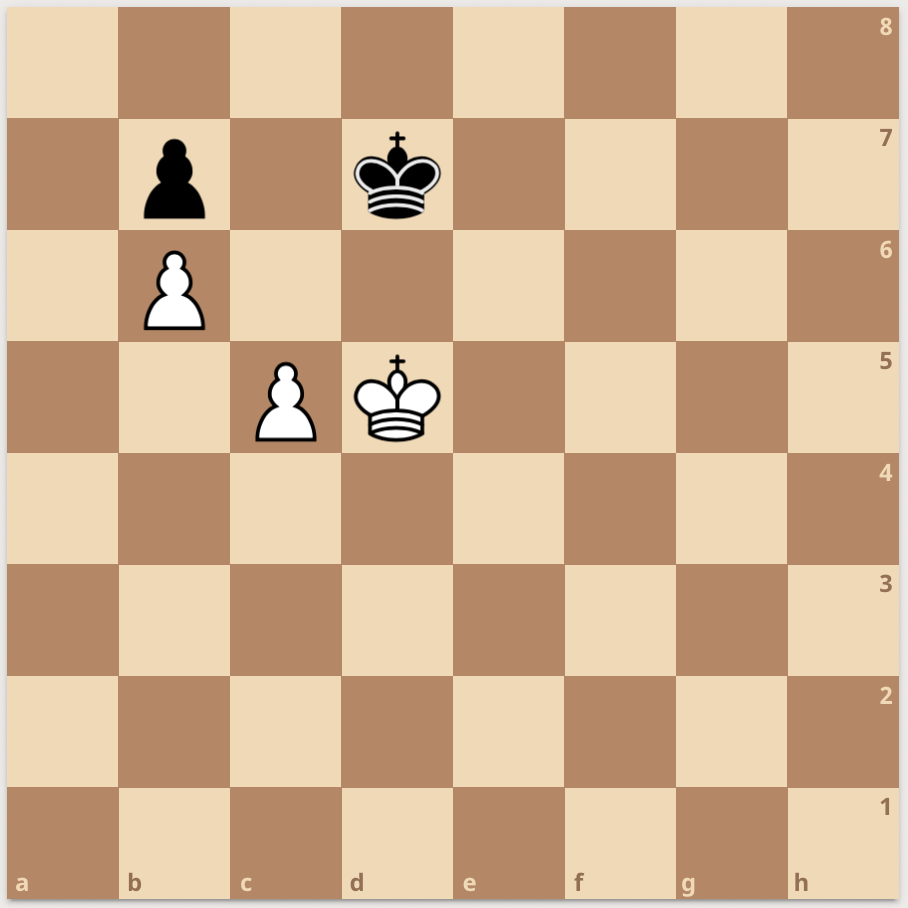

Sometimes, it's also desirable to lose a tempo. This often comes up in the endgame, when the kings become two of the strongest pieces on the board. Let's look at this position (from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Triangulation_(chess)):

White to move

Here, White would win the game if only it were Black's move, because Black would be forced to move their king away and allow White to press in and force one of their pawns to be promoted. However, since it's their move, White can't do that. Instead, they need to lose a tempo by triangulating their king -- moving their king in a triangle to arrive back in this position but having it be Black's move. They can accomplish that like this:

1. Ke5!

Which Black must, for practical purposes, respond to by trying to win a pawn:

1. ... Kc6

But White can still move to protect the pawn:

2. Kd4

And the Black king is forced to retreat:

2. ... Kd7

Finally, White can move their king back to where it started, except now it will be Black's turn to move:

3. Kd5

Black now has no choice but to move their king, and any move they make leads to them losing the game. Black's position, in which they would prefer not to make a move and simply pass their turn, but they are compelled to move nonetheless by the rules of the game, is called "Zugzwang," which means "compulsion to move" in German.

Finally, I'll reiterate that tempo is connected to many other important analytical components of chess. For example, it is often possible to trade material -- pieces on the board -- for tempo, by letting an opponent capture a piece in order to make an extra move somewhere else on the board. Tempo can also be traded to gain developmental or positional advantages. Deftly gaining, managing, and trading different kinds of advantages for others is a major component of what makes a chess player great.

Tempo Analogies Between Chess and Magic

Magic, like most other games, also has a notion of tempo. As it is usually described, "tempo plays" in Magic do something to prevent or undo the actions of your opponent in some way, and "tempo strategies" seek to exploit tempo plays by furthering a player's path to victory because of the efficiency of the tempo plays.

These are good ways to think about tempo, but relating tempo in Magic back to tempo in chess is also enlightening. It can also help clarify what tempo is in Magic because tempo is a simpler concept in chess, and the concept of tempo in Magic is often somewhat nebulously described or understood, or at least it is confounded because of the complex nature of tempo in Magic.

In chess, tempo is simple because every player gets one tempo every turn, they have to spend that tempo every turn, and all moves cost one tempo. They can trade tempo for other advantages too, and they can also make moves that waste tempo (intentionally or otherwise), but they still get just one tempo a turn they need to manage. Tempo is the unit of potential energy. It is the measure of how a player is able to make decisions that impact the progress of the game. In chess you alternate making decisions with your opponent.

In Magic, the ability to affect the game (usually) is defined by a player's ability to cast spells. The way a player (usually) casts spells is by spending mana, and the way they acquire mana to spend is (usually) through playing and tapping lands. Looking at the mana a player has available to use is (usually) a pretty straightforward way to assess the amount of tempo they gain every turn. Unlike chess, where a player always receives one tempo per turn, a Magic player receives a variable amount of tempo depending (mostly) on how much mana they can spend. And complicating matters are all those "usually's" and "mostly's," because the number of decisions a player can make per turn is much, much higher in Magic than in chess, and many individual mechanics or cards violate some of these basic statements.

Like chess players, Magic players often exchange tempo for other kinds of advantages. For example, a player may spend some tempo (mana) to cast a creature and develop their position (board state). Or, they may spend some tempo (mana) to cast a spell that draws more material (cards). Or, they may spend some tempo (mana) to try and deprive their opponent of some of their tempo (mana) by destroying the lands that produce it. In Magic, like in chess, tempo (mana) is potential energy, the ability to affect the game state.

Unlike chess players, Magic players can hold tempo (mana) in reserve, and spend it on certain special kinds of moves (instants and instant-speed effects) on their opponent's turn. Their tempo (mana) also comes in a few different types (colors), and they have to have the right kind of tempo (mana) to make most moves. If they have enough tempo (mana), they can also make multiple moves in a single turn. And, they can never be in a Zugzwang position, because they always have the opportunity to pass and let the tempo (mana) they could have gained (lands they could have tapped) go unused without any direct penalty for doing so.

In addition to the rough "tempo == mana" analogy, the other analytical quantities of chess also have analogues in chess: "material == card advantage", "development == spells played", "position == board state". In both chess and Magic, the analytical qualities are interrelated, can be traded for each other, and deftly gaining, managing, and trading them is what makes a great player. In fact, the reason chess and Magic are both such great, rich games is precisely because of these relationships. It makes them complex and hard to solve optimally, providing players the opportunity to study and think and be creative and leverage experience to achieve greater and greater overall play skill.

Tempo in Old School Magic

Finally, we come to some specific examples of tempo in Old School Magic. I am no Pro Tour player and you're not going to find me dominating FNM's, but within the domain of Old School I can speak to what tempo means in that card pool. Also, because that card pool is much simpler than Magic writ large, it's easier to talk about tempo without things like Planeswalkers or Dredge or alternate casting costs completely violating all of the analogies I just described.

Let's start with perhaps the quintessential tempo card: Unsummon.

Get CARD'ed, fool

Unsummon is a bargain in the tempo department. For the low price of one blue mana, you can return absolutely any creature your opponent has played to their hand. Factory, Dib, Serra, a very stuffed Atog, even a big ol' Elder Dragon. Granted, you also have to spend a card (material) to do it, but it can be a very large tempo swing. You are directly undo'ing the board state (development) your opponent spent mana (tempo) to create, and you are netting a mana (tempo) advantage proportional to the difference between the mana (tempo) your opponent spent to achieve that board state (development) and the mana (tempo) you spent to undo it.

But Unsummon is not a winning strategy on its own. To really take advantage of Unsummon, you need to be able to exploit the difference in tempo you've created. Since you are putting a card in your graveyard and your opponent is getting their card back, Unsummon is really only good if having that creature off the board for one extra turn could win the game. What strategies are like that? Combo and fast aggro decks, certainly. Maybe prison decks too. But control or midrange, probably not. Those decks tend to emphasize card quality and advantage (material), and don't really care about one extra turn. Further complicating the matter, Unsummon can be used (often correctly) on your opponent's turn, which means you need to speculatively leave tempo unused, and ideally also have a way to use that tempo for something else if you end up not needing to cast the Unsummon. So it comes with a possible opportunity cost in tempo as well.

A spell that is essentially exactly like Unsummon from a tempo standpoint, but without needing to sacrifice a card to do it, is the best removal spell in the format, Swords to Plowshares.

Remove from the game ENTIRELY, foolio

Swords also costs one mana and gets rid of the creature (development) you are trying to undo, but it removes it from the game instead of putting it back in your opponent's hand. Thus, unlike Unsummon, it does not come with a card advantage (material) cost. It does gain your opponent some life, which maybe seemed like a reasonably equal design difference compared to Unsummon to Wizards during alpha, but we now know the power level of these two uncommons is very different because going down a card is much more impactful than your opponent gaining some extra life (usually). Unlike Unsummon, where only decks that are really designed to care about tempo want it, just about every deck would want to be able to play Swords if the mana works, because it can produce a massive tempo advantage with no card advantage cost.

Relatedly, and I feel like it's OK to mention this since Scryings came out, Man-o'-War is another very strong tempo card.

Apostrophe hyphen is some punctuation tech

Whereas Swords spends a card to remove a card in pursuit of a tempo advantage, Man-o'-War actually leaves an extra card behind. It costs more tempo (mana) to use so the potential tempo gain is less than Swords, but it comes with a development advantage in exchange. This means it has a more narrow appeal in terms of decks that want it, but in the decks that do want it, this is one of the best cards. It does everything you want. Plays a threat, bounces a threat, and usually generates tempo. Unfortunately, it says just "return target creature" rather than "you may return target creature," which creates edge cases where it is literally uncastable, but in aggro or midrange decks that are racing, it can be absolutely backbreaking.

Another kind of spell trades card advantage for tempo directly, like Dark Ritual.

This guy seems like he likes tempo

Dark Ritual makes mana, and mana is essentially directly convertible to tempo in Magic, so it creates an ability to apply tempo to affect the game state sooner than would otherwise be possible. In exchange, you also lose a card, which modern Magic players know can be pretty important. Going Swamp > Dark Ritual > Hippie only to see your Hippie bolted is straight card disadvantage. But nonetheless, for decks which want the tempo more than the card (remember the kinds of decks that want Unsummon?), Dark Ritual can be an amazingly powerful card.

Incidentally, Black Lotus is a very similar card to Dark Ritual from a strategic role perspective, with its main advantages over Dark Ritual being that Black Lotus generates three free mana instead of two, doesn't require a specific kind of tempo (black mana) to activate, and the tempo (mana) it generates may be of any color (universal tempo) instead of just Black (narrow tempo). In some decks, like say mono-black, the relative value of Black Lotus and Dark Ritual is actually pretty close. The main difference is whether netting two mana or three mana is a big deal, and in mono-black, there are times when that is relevant (Mind Twist, Juzam Djinn) and times when that is not (Sinkhole, Hymn, Hippie). In other decks, like decks with lots of 3-4+ drops or color requirements other than black, there is a huge difference between the two. This is the reason why outside mono-black, very few decks want Dark Ritual, but most decks want Black Lotus.

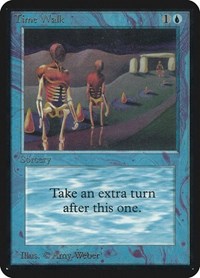

Now let's look at a card that even declares its purpose is manipulating time: Time Walk.

You might not know it to look at me, but I can run really, really fast

Time Walk lets you take an extra turn, which lets you do a lot of things. Draw a card (which is card advantage neutral, since you had to spend a card to cast Time Walk), play a land (add a possible tempo generator), attack again (leverage board state), and cast more spells (spend tempo develop your position). In the late game, one of its biggest impacts is letting you gain a whole bunch of tempo (mana) for the low price of two mana.

Since you get a second turn in a row, you have the ability to use any lands you already have deployed twice, effectively doubling your tempo holdings. A late game Dib+Time Walk into Serra can often be the ballgame, without even factoring in the extra attack phase. Or, an extra turn to spend mana on things like Icy Manipulator or Jayemdae Tome can lead to a lethal attack or insurmountable card advantage. Time Walk is many things, but chiefly, it is an opportunity to spend a couple tempo to make many more tempo. This explanation is also partly why it feels so bad to merely use Time Walk as an explore in the early game. It's capable of so much more than that. The opportunity cost of using it to explore is very high.

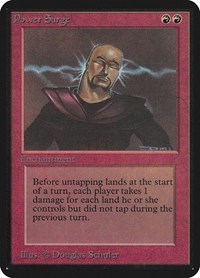

Last but not least, there are cards which alter the nature of tempo in Magic. One example is Power Surge.

Wait, is that Scott or Mark?

In Old School, with mana burn still a rule, Power Surge creates the potential for Zugzwang. Instead of being able to pass for free and leave some tempo (mana) unused, you are now punished for doing so. In a world without mana burn, you could just frivolously waste all your tempo (mana) by tapping it and letting it drain out, but not in Old School.

Power Surge plus mana burn creates a use-it-or-else Zugzwang dynamic for many decks. Power Surge decks are designed to have lots of outs to avoid the Zugzwang themselves, while punishing "normal" decks that are well designed around principles like mana efficiency or interactivity. Dedicated aggro or control decks tend to have problems with a resolved Power Surge, for example, because they, respectively, have too good/low of a curve to spend all their tempo, or rely too much on holding up tempo to prevent their opponent from achieving their goals. Even more so, when combined with Manabarbs, Power Surge decks punish people for even having tempo to use in the first place, creating a damned-if-you-do-damned-if-you-don't kind of Zugzwang that is not escapable under the rules of Old School Magic.

Conclusion

Tempo is a concept that can be analyzed in many games, ultimately relating back to how the game provides players the ability to affect the progress of the game. For practical purposes, tempo often relates to turns or some other measure of time in the game. In chess, turns are simple constructs which require players to acquire and spend one tempo each turn to make a move. In Magic, turns are complex constructs where players choose from many possible actions, and an additional underlying resource, mana, means players gain different amounts and kinds of tempo each turn, complicating the decision landscape available to them. But nonetheless, by understanding the fundamental meaning of tempo in chess, it is possible to more deeply understand how time, potential, and game actions relate back to tempo in more complex games such as Magic.